The records of the Clerk of Civil District Court’s Office, which date back to the 1700s, represent the rich history of New Orleans and its diverse communities. Our archives can be used for property, family history, architectural, and landscaping research.

When one thinks of New Orleans, one of the first things that comes to mind is Mardi Gras. Over the years, Carnival has become one of the most recognizable celebrations in New Orleans and Louisiana culture. The New Orleans Mardi Gras Season begins on January 6th, known as Twelfth night or the Feast of the Epiphany for many Christian denominations. The celebrations last through Mardi Gras day, the date of which changes from year to year depending on the Christian liturgical calendar and the position of the holy day of Ash Wednesday.2

The origins of Mardi Gras can be traced back to Medieval Europe to celebrations in both Rome and Venice. The tradition travelled to France in the 17th and 18th centuries and then spread to the French colonies. On March 2, 1699, French-Canadian explorer Jean Baptiste Le Moyne Sieur de Bienville arrived on a plot of land south of New Orleans and named it Pointe du Mardi Gras when he and his men realized that it was the eve of the holiday. In 1702, Bienville established Fort Louis de la Louisiane, now Mobile, Alabama, and in 1703 the settlement celebrated America’s very first Mardi Gras. Bienville founded the City of New Orleans in 1718 and by the 1730s, the festival of Mardi Gras was celebrated openly throughout the city. A century later, New Orleans Carnival celebrations featured street processions of maskers with carriages and horseback riders. The concept of floats and masked balls were introduced in 1856 and the first recorded evidence of Mardi Gras “throws” came in 1871.3

However, from these early years up until the 1990’s, Mardi Gras was an extremely segregated event. Krewes, events, and parades were often divided along color lines, with African Americans being barred from joining many of the traditionally white krewes and prevented from having their own krewes parade along the same routes as the white ones. In fact, it was not until Emancipation, the end of the Civil War and the passing of the 13th Amendment that African American people were even legally allowed to congregate without intense supervision or participate in Mardi Gras festivities. 4 Due to these restrictions, many communities rallied together to form their own traditions and solidified themselves as culture bearers for the City of New Orleans.

In celebration of Black History Month and the Mardi Gras Season, The Clerk of Civil District Court’s Office would like to highlight a selection of our city’s culture bearers. While looking at the history of these groups, we would also like to highlight our collection of notarial records, such as acts of incorporation, property sales, and property transfers, that illustrate how these groups formed and interacted with their communities. During this month, we will focus on three particular New Orleans culture bearers: the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club, the Mardi Gras Indians, and the Jugs Social Club-Krewe of NOMTOC. All of these organizations have a fascinating history and illustrate how the African American community in New Orleans came together to form their own traditions that have since diffused into the broader culture of the city. It also shows how each of these groups are more than just Mardi Gras organizations, but often charitable organizations that offer assistance and outreach to their communities. The first culture bearer we will highlight is the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club.

Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club- Krewe of Zulu

As previously mentioned, prior to the Civil War, open gatherings of enslaved people were strictly controlled or banned altogether. Following the end of the war and the passing of the 13th Amendment, public demonstrations and celebrations among groups of African Americans became legal and African American people in New Orleans were able openly to celebrate Mardi Gras and form their own traditions. The social aid and pleasure club was one such tradition that developed during the years following the end of the Civil War. Following Emancipation, formerly enslaved people were left financially crippled. Many people wished to give their family members proper burials, but were unable to afford the costs to do so. To combat this issue as well as others facing their communities, African Americans began to form benevolent societies that would hold social events to raise money for various causes that would benefit the members of their club.6

In this tradition, a group of African American workers began to gather in their “backatown” homes; the area encompassing the faubourgs of Tremé and Bayou St. John, around 1901.8 These men formally organized into a benevolent society called “The Tramps” and held informal parades and parties during the Mardi Gras season. In 1909, a travelling theatrical company brought a comedy entitled “Smart Set” to the Pythian Theater. “Smart Set” contained musical numbers set in a Zulu village and presented visuals of strong Zulu warriors clad in grass skirts and carrying spears. One of the men who saw the show was John L. Metoyer, a member of “The Tramps.” Metoyer was inspired by the visual imagery of the show. He was particularly inspired by one of the lyrics where a Zulu king declared “There never was and there never will be another king like me!” Embracing these visuals and sentiments, Metoyer organized fifty men into the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club and held their first parade in 1910.9 During this first parade and all subsequent parades, members mimicked the images that Metoyer witnessed in the “Smart Set” play. Members donned grass skirts, blackface, bushy wigs, and elaborate headpieces in an effort to embrace black identity by connecting themselves to the actual Zulu Tribe on the African continent, while also taking a revolutionary step to mock the white-created caricatures of black identity that were prevalent during the period.10

During its early years, Zulu paraded in the “backatown” area of New Orleans which was made up of primarily black neighborhoods. Segregation laws forced Zulu and other African American carnival organizations to remain in this area, but the area embraced the traditions. Neighborhood bars would sponsor floats and advertise that the parade would stop at their establishment, as the sponsored floats were obligated to pass their patron’s bar. This meant that the parade did not have a set route as floats would go in different directions to fulfill their obligations. 11

After six years of parading, the men of the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club appeared before the notary Gabriel Fernandez on September 20, 1916 to officially incorporate. According to Article I, “the name and title of this corporation shall be the Zulu Social, Aid and Pleasure Club and by the said name the said corporation shall have power and authority to contract, sue and be sued; to hold, receive, lease, mortgage, acquire, or in anywise alienate property both real and personal and mixed; to aid the sick; and make and establish such rules, laws, and regulation for the management and promotion of the interest, the same to alter, amend or repeal at pleasure.” Article III of the incorporation states that “the purposes and objects of this corporation shall be for social purposes, to establish between its members ties of friendship and sociability; to establish between them aid and esteem for the promotion of good fellowship and friendly intercourse between the members and their guests and to do all things necessary to advance the purposes and objects above set forth.” This stated purpose is consistent with those of social aid clubs that came before them as well as those who were Zulu’s contemporaries. The articles described are shown below.

This act of incorporation was signed by twenty-five members of the organization, including club president Thomas English and John Metoyer, who was the eighth member to sign.

Zulu remained a popular parade and organization until the 1960s. During the civil rights movement, it became unpopular to be a member of Zulu as it was seen as increasingly controversial to dress in grass skirts and don blackface, no matter the intentions of the club. Many black organizations protested against Zulu, causing membership to dwindle to around sixteen men. Toward the end of the decade, Zulu’s popularity was back on the rise, much to the credit of James Russell, who was president during this period. In 1968, Zulu was granted permission to parade along St. Charles and Canal Streets, the route assigned to Rex and other traditionally white parades.12

Zulu saw an uptick in popularity during the 1970s and 80s. This was due to the work and contributions of Roy E. Glapion Jr., who served as the Zulu president from 1973 until 1988. In 1973, Zulu became the first parading krewe in New Orleans to integrate, nineteen years prior to a city ordinance requiring the desegregation of krewes in 1992.14 Glapion also made significant efforts to support the community, returning to the charitable origins of the club. During his tenure as president, Zulu members volunteered to feed the needy during the holiday season and organized fundraisers for sickle-cell anemia research. They established a gospel choir and also reached out to young people through youth organizations and partnerships with local schools.

Also during Glapion’s tenure as president, The Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club began to buy property as an organization, mostly within Square 339 of the Second District. The first of these sales occurred on July 14, 1977 before Notary John S. Keller.

In this sale, Edward Leblanc Jr, Ronald Ruiz, Carl Nogess, and Herbert Jones sold Lot “C” of Square 339 in the Second District at the municipal address of 732-734 North Broad Street to the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club, Inc., represented by Roy E. Glapion Jr., for a sum of $57,000.

In the legal description of the property, seen in the image above, there is mention of a 1927 survey of the property by W. J. and G. J. Seghers, deputy city surveyors, annexed to an act before notary Daniel J. Murphy dated March 25, 1927. That survey can be seen below.

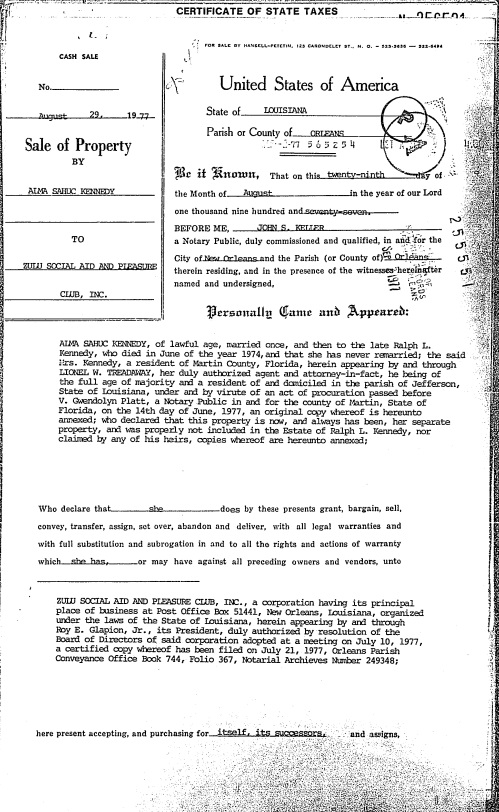

From 1978 onward, the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club would use the building and property at 732-734 North Broad Street as their headquarters. Also in the same year as the purchase of 732-734 North Broad Street, the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club purchased 2648-50 St. Ann Street. Zulu, once again represented by Roy E. Glapion Jr, purchased the property designated as “Lot 3 in Square 339 in the Second District,” from Aima Sauhuc Kennedy, on August 29, 1977, before Notary John S. Keller. This property was in the same square as the previous property.

The following decade, in 1986, Zulu, again represented by Glapion, appeared before Notary Jesse S. Guillot on January 24 to purchase “Lot A of Square 339 in the Second District,” listed as 722-24 North Broad Street, from Cardas Inc.

Attached to this act is a survey of the property dated February 21, 1985 from Sterling Mandle, Land Surveyors, which is mentioned in the property description above and can be seen below.

On May 24, 1991, three men from the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club, Inc. appeared before Notary John S. Keller, a favorite of the organization, to amend the original Articles of Incorporation from 1916. In this amendment, it states that “it was resolved that all Articles of the original and amended Articles of Incorporation of the ZULU Social Aid and Pleasure Club, Inc. be deleted and that the following articles be substituted as the Articles of Incorporation of ZULU Social Aid and Pleasure Club, Inc.”

In Article 3 of the new incorporation, it is specified that the purpose of this club is “to establish between it’s members ties of friendship and sociability; to establish between it’s members esteem for the promotion of good fellowship.” The rest of the article also lists other privileges that the corporation maintains and can be seen in the image below.

These new articles were signed by James A Wright, President of Zulu; Frank Boutte, Vice President; and Phillip M. Baptiste, Recording Secretary who served as the representatives of the club for this amendment.

In 2002, the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club resumed buying property in Square 339 in the Second District, as they had under the leadership of Roy E. Glapion Jr. This time Zulu, represented by Brother Gary A. Thornton, Zulu President, purchased “Lot A,” designated as 2644-46 St. Ann Street, for the price of $22,500, from Kristopher Lloyd Shaw, before the notary Paul A. Bello on June 28, 2002.

This act also reveals that, in addition to the payment of $22,500, Zulu also “authorizes and assigns two rider positions on its Friends of Zulu Float for the use of the Vendor (Shaw) and his guest for the Krewe of Zulu parade on Mardi Gras 2003, and shall provide vendor and his guest with costumes.” That rider positions in the parade could be offered as a form of additional payment in a sale of property speaks to the popularity of Zulu during the early 2000s as well as their status as culture bearers.

2010 brought forth an interesting opportunity for the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club. In an Act dated April 14, 2010, Zulu entered into a cooperative endeavor agreement with the City of New Orleans. According to Article VII, Section 14(C) of the Louisiana Constitution, “any political subdivisions and political corporations may enter into a cooperative endeavor agreement with any public or private association, corporation or individual to carry out a local infrastructure project to achieve a public purpose.”15 In this agreement, the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club sought to demolish existing buildings in the Square 339 in order to build a 7000 sq. ft. facility to go with their existing 3600 sq. ft. headquarters. Zulu claimed that building this new facility would not only “facilitate and accommodate the needs to the membership,” which exceeded 500 members at the time, but the space could also “be used for receptions, meetings, weddings, parties, and community affairs,” making it a perfect candidate of a cooperative endeavor with the city.

In the related zoning docket for this project, approved on April 26, 2010, there is a plan for the project that shows the existing headquarters at 732 North Broad, the proposed parking spaces behind it, and the new building that would be located at 722-24 North Broad.

The new building that was erected was named for the famed president, Roy E. Glapion Jr., in honor of all he did for the organization. Zulu continues to be one of the most recognizable krewes and one of the most popular parades during the New Orleans Mardi Gras celebrations solidifying their place in the cultural fabric of the city. They continue to make their presence known in the community through their charitable acts and events.

This Mardi Gras, the Krewe of Zulu is set to roll on Mardi Gras Day, Tuesday, March 1st at 8:00AM. Check out our next Culture Bearers blog on the Mardi Gras Indians on February 11th.

The Clerk’s Office has a rich amount of history pertaining to various different New Orleans culture bearers and carnival organizations. If there are any particular interests that you would like to learn more about, please contact the Clerk’s Office. We are happy to assist.

References:

- “Krewe of Zulu,” Mardi Gras New Orleans, accessed January 25, 2022, https://www.mardigrasneworleans.com/parades/krewe-of-zulu.

- Carolyn Heneghan, “A Brief History of Mardi Gras in New Orleans,” North America/USA/Louisiana, Culture Trip, accessed January 5, 2022. https://theculturetrip.com/north-america/usa/louisiana/articles/a-brief-history-of-mardi-gras-in-new-orleans/.

- “Mardi Gras History,” Mardi Gras New Orleans, accessed January 11, 2022, https://www.mardigrasneworleans.com/history/.

- Nile Pierre and Hugo Fajardo. “Mardi Gras in color: revealing the historical divide of krewes,” The Tulane Hullabaloo, last modified January 31, 2018, https://tulanehullabaloo.com/35981/intersections/mardi-gras-color-revealing-historical-divide-krewes/.

- Doug MacCash, “Zulu will not crown a king in 2021; ‘historic moment,’ krewe says,” NOLA.com, accessed January 5, 2022, https://www.nola.com/entertainment_life/mardi_gras/article_aca6e8d8-3663-11eb-ba5b-77c788547c92.html.

- Edward Branley, ” History of the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club” Best Local Things to Do, Go Nola, accessed January 6, 2022. https://gonola.com/things-to-do-in-new-orleans/mardi-gras-history-zulu-social-aid-pleasure-club.

- Edward Branley, ” History of the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club” Best Local Things to Do, Go NOLA, accessed January 6, 2022. https://gonola.com/things-to-do-in-new-orleans/mardi-gras-history-zulu-social-aid-pleasure-club.

- Edward Branley, “NOLA History: Backatown and the Evolution of New Orleans Neighborhoods,” History, Go NOLA, accessed January 12, 2022, https://gonola.com/things-to-do-in-new-orleans/history/nola-history-backatown-and-the-evolution-of-new-orleans-neighborhoods

- Edward Branley, ” History of the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club” Best Local Things to Do, Go NOLA, accessed January 6, 2022. https://gonola.com/things-to-do-in-new-orleans/mardi-gras-history-zulu-social-aid-pleasure-club.

- Trimiko Melancon, “The Complicated History of Race and Mardi Gras,: Black Perspectives, last modified February 9, 2018, https://www.aaihs.org/the-complicated-history-of-race-and-mardi-gras/.

- “History Of the Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club” History, Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club, accessed January 3, 2022, http://www.kreweofzulu.com/history.

- “History Of the Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club” History, Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club, accessed January 3, 2022, http://www.kreweofzulu.com/history.

- “Roy E. Glapion Jr.,” Find a Grave, accessed January 10, 2022, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/84728328/roy-e.-glapion.

- Trimiko Melancon, “The Complicated History of Race and Mardi Gras,: Black Perspectives, last modified February 9, 2018, https://www.aaihs.org/the-complicated-history-of-race-and-mardi-gras/.

- “2014 Louisiana Laws Revised Statutes TITLE 33 – Municipalities and Parishes RS 33:7633 – Cooperative endeavor agreements,” Louisiana Laws, Justia, accessed January 7, 2022, https://law.justia.com/codes/louisiana/2014/code-revisedstatutes/title-33/rs-33-7633/.