National Archives Month is just around the corner in October! Check out our website at orleanscivilclerk.com for the latest and upcoming virtual exhibits, which can also be viewed in person at the Notarial Archives Research Center, 1340 Poydras Street. For 2021’s Archives Month, the office will present exhibits on cemeteries and their association with benevolent society tombs, and on jazz figures and musical venues. The office will also offer related tours and educational workshops. For more information, contact the Research Center at 504-407-0106 or civilclerkresearchctr@orleanscdc.com.

The records of the Clerk of Civil District Court’s Office, which date back to the 1700s, represent the rich history of New Orleans and its diverse communities. Our archives can be used for property, family history, architectural, and landscaping research.

The Clerk’s Office holds numerous charters of benevolent associations and social aid and pleasure clubs, which date back to the 1800s.

Benevolent Societies

Benevolent societies (used interchangeably with associations) stemmed from ideals of the Protestant religious revival known as the Second Great Awakening (1795-1835) and as a response to the American Revolution.1 These ideals included altruism and charity,2 with the main purposes of the societies to provide benefits and aid to its members. Benefits typically consisted of funding for funerals, burials, sickness, and aid for widows and orphaned children.3 Other advantages included facilitating access to social services and providing an outlet for social activities and a sense of community.

The oldest benevolent society still in existence in New Orleans is the Fireman’s Charitable and Benevolent Association, which dates back to the 1830s.4 This organization is responsible for the creation of the Cypress Grove and Greenwood Cemeteries and known for the Firemen’s Monument in Greenwood Cemetery.5

https://tclf.org/greenwood-cemetery-la

Benevolent associations, not to be confused with social aid and pleasure clubs, became increasingly popular in the 1800s and expanded to include fraternal, literary, political, religious, and many other purposes for organizing. These societies “…erupted across racial, gender, and socioeconomic lines.”6

After the American Revolution and into the 19th century, the majority of associations were chartered by women, usually from wealthy backgrounds. “By 1830 nearly every town and city had a female benevolent society (often the only benevolent society in a particular community), and many had several [benevolent associations].”7 The bulk of these societies operated by women were chartered with religious purposes and to provide charity and relief to those in need.8

The benefits of membership, the philanthropy, and sense of community were so appealing that “…in the final decades of the nineteenth century societies became an integral part of life in the city for both blacks and whites, and by that time [benevolent associations] were everywhere. An estimated four-fifths of the local population belonged to such groups.”9

The Ladies Apostolical of New Orleans Society

Of the numerous charters housed in the Notarial Archives Research Center, the following is an example of a women’s organization, the Ladies Apostolical of New Orleans.

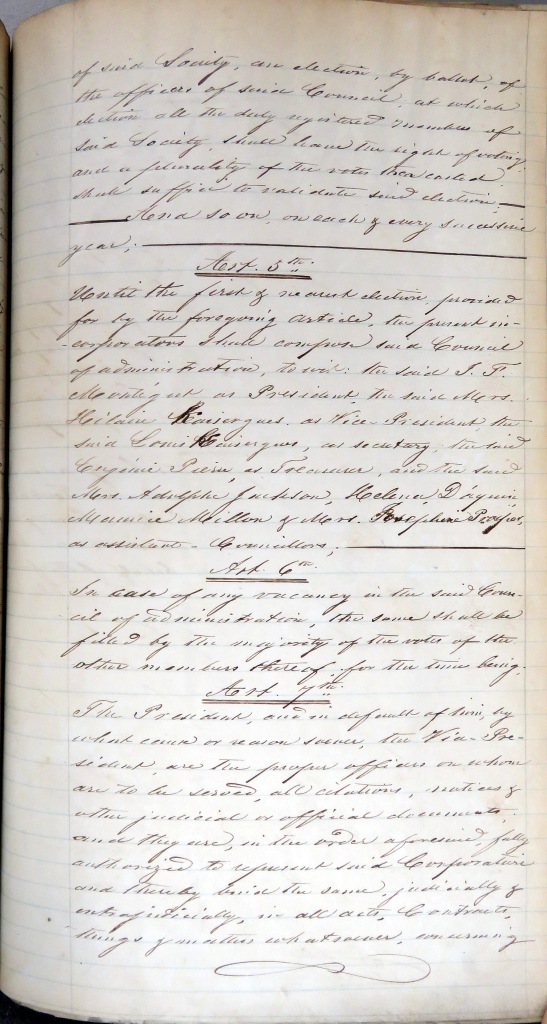

The following individuals: Joseph F. Montegut, Louise Cayetano Kaisere [also spelled Caiseregues on the signature page], Louis Kaisere, Eugenie Pierre, Celestine Jackson, Helena Daquin, Adelaide Baptiste Milton, and Josephine Prosper came before notary, Octave De Armas, on July 24, 1872, to charter their organization, the Ladies Apostolical. According to the charter, the ladies declared that they had been a society of mutual aid and benevolence since October 17, 1863.

The society further explained that they wished to incorporate in order to enjoy and exercise the rights, privileges, and advantages that were granted by the state to corporations such as their own.

The Ladies Apostolical stated their purpose of their organization was for “…acts of mutual aid and benevolence among the members thereof.”

It is interesting to note that in Article Five (above) some members of the first “Council of administration” until the nearest election were men. Joseph F. Montegut would serve as president, and Louis Kaisere would serve as secretary. The other positions were filled by some of the aforementioned women. Louise Kaisere would be the vice president for the organization, and Eugenie Pierre would be the treasurer. The remaining ladies were named as “assistant councilors.”

Article Nine states, “the said incorporation hereby declares and acknowledges that a certain tomb or monument erected in the Catholic Cemetery [St. Louis No. 2] bounded by Claiborne, Bienville, Custom House [now Iberville], and Robertson Streets, on behalf of the former unincorporated association, is the lawful property of the one hereby incorporated.”

The charter is concluded with the standard remarks about the act being passed in the notary’s office in the presence of witnesses and is followed by the signatures and marks of the parties to the act, the witnesses, and the notary.

The reader may notice that all of the women, with the exception of Eugenie Pierre, did not have the ability to sign their names. The notary had the women sign with an “x,” and then he identified the respective mark of each woman by writing her name.

In the 1800s, it was common that one or multiple parties to the transaction were unable to sign their name. The notary would determine that the party was illiterate and would be required by law to read the act aloud. Parties unable to sign their names would sign with a mark.

Further research by way of census records and city directories reveals that this society was chartered by women of color.

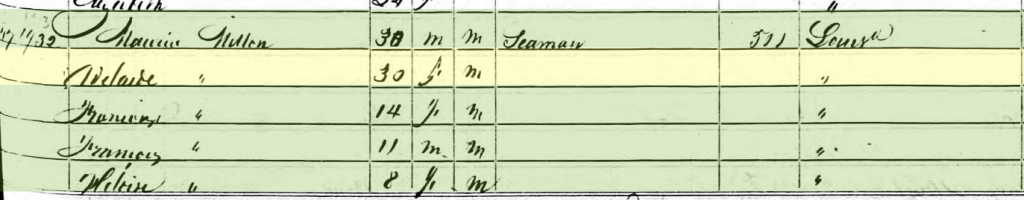

In the 1850 census, Adelaide Milton is noted as a 30-year-old mulatto woman who was born in Louisiana. Other members of her household are included, particularly Mannie Milton who is named as her husband in the charter.

1850; Census Place: New Orleans Municipality 1 Ward 5, Orleans, Louisiana; Roll: 236; Page: 221a

Louise Cayetano [Kaisere/Caiseregues] is listed as a free woman of color (f.w.c.) living on Bayou Road according to the 1861 City Directory.

Ancestry.com. U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

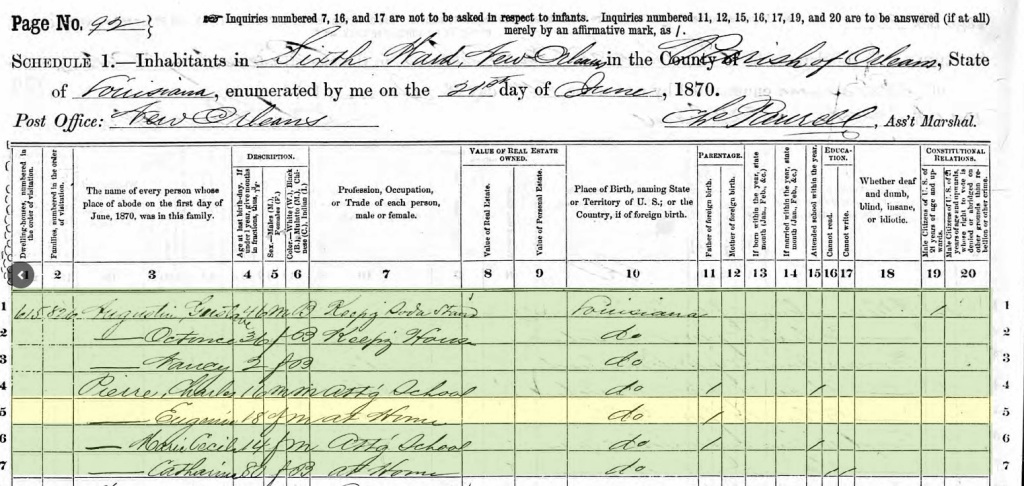

Helena Daquin is registered as an 18-year-old mulatto woman in the 1870 census.

1870; Census Place: New Orleans Ward 8, Orleans, Louisiana; Roll: M593_523; Page: 710A

Eugenie Pierre is also recorded as an 18-year-old mulatto woman in the 1870 census.

1870; Census Place: New Orleans Ward 6, Orleans, Louisiana; Roll: M593_522; Page: 330B

Lastly, Joseph [Ferdinand] Montegut is listed as a 59-year-old mulatto male with the occupation of book keeper in the 1880 census. His wife, Carmelita, and two sons, Joseph and Ferdinand are also recorded below.

1880; Census Place: New Orleans, Orleans, Louisiana; Roll: 461; Page: 218A; Enumeration District: 035

Another important function of associations was often the provision of a society tomb as a means for “…a respectable aboveground burial for individuals from a variety of ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds who did not have access to a family tomb and could not afford their own private oven vault.”11

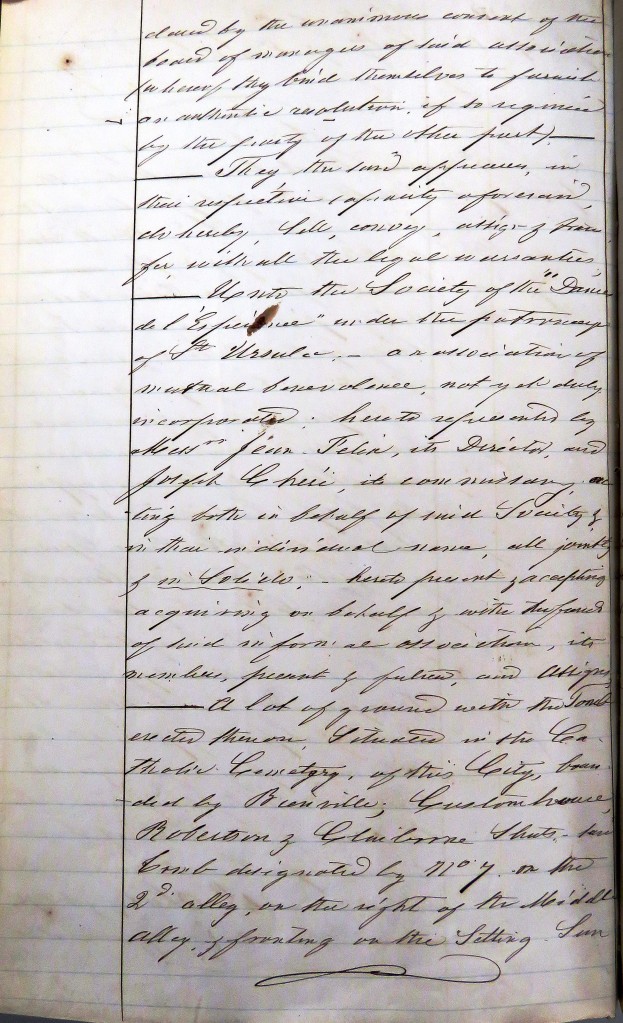

Below is an example of a tomb sale by the Ladies Apostolical (written in French as “Les Dames Apostoliques”) to another benevolent society, “Les Dames de l’Esperance” (Ladies of Hope). The act of sale was executed by the previously mentioned notary, Octave De Armas, on September 9, 1880.

Notice in the image above, Joseph Ferdinand Montegut was recorded as the director, Mrs. [Louise] Widow Hilaire Caiseregues was the president, and Mrs. H. Macarty was listed as the treasurer. At the bottom of the page, there is a reference to the July 24, 1872 charter of the Ladies Apostolical.

The act states that the Ladies Apostolical wished to sell a [single] lot of ground with the tomb located in the “Catholic Cemetery” (St. Louis No. 2 as indicated by its binding streets) unto the Ladies of Hope, an unincorporated society “under the patronage of St. Ursula” as represented by its director, Jean Felix, and its commissary, Joseph Chere. The tomb was “designated by no. 7 on the 2nd alley on the right of the middle alley, and fronting on the setting sun.”

The third page of the act states where the Ladies Apostolical acquired the tomb and lot of ground. The tomb was purchased from G. Carriere and P. Benoit in an act of sale executed by notary, Octave De Armas, on December 16, 1874. Since this tomb was acquired two years after the society chartered, one can conclude that the Ladies Apostolical had two tombs, one being the tomb initially mentioned in the 1872 charter.

The Ladies of Hope agreed to purchase the tomb and ground for $330.

The act of sale concluded with signatures and the notary’s remark that the women were unable to sign for themselves and had acknowledged the sale with their mark after the notary read the act aloud.

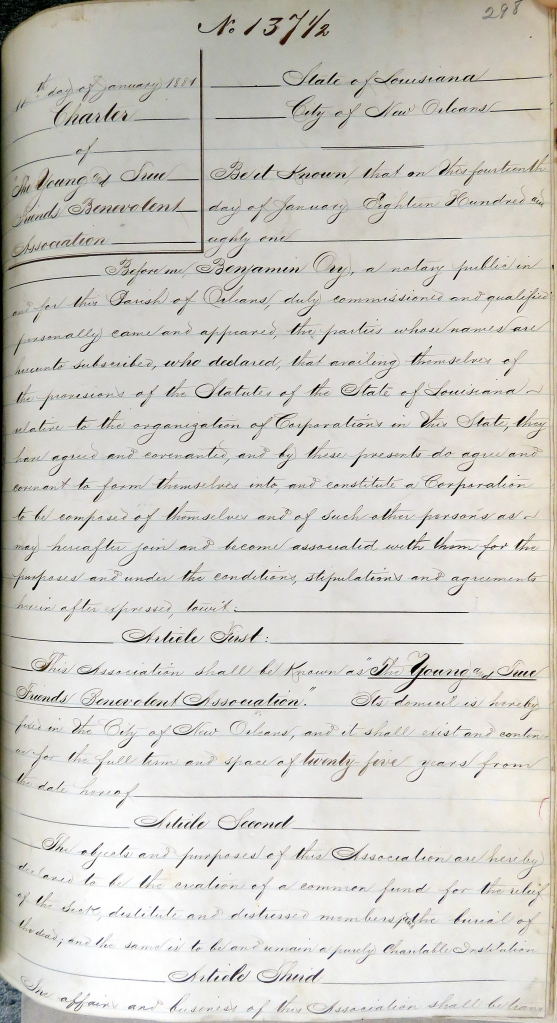

The Young and True Friends Benevolent Association

In addition to society tombs, benevolent societies were also known for “street parades that led to funerals or fanciful tomb dedication ceremonies in the cemeteries.”12 The popularity of funerals with music (or jazz funerals as they would later be recognized) began to rise around the same time as benevolent associations, and thus many associations began incorporating them as a tradition.13

Below is the charter of one such early organization that helped establish the tradition of jazz funerals.

The Young and True Friends Benevolent Association was chartered on January 11, 1881, before notary, Benjamin Ory. The purposes of the association was to create a “common fund for the relief of the sick, destitute, and distressed members, and the burial of the dead, and the same is to be and remain a purely charitable institution.”

In Article Three, the association declared that the affairs and business of the organization should be “transacted by a quorum of members.” The executive officers consisted of president, first and second vice president, recording secretary, assistant recording secretary, financial secretary, treasurer, grand marshal, and sergeant at arms. The names of the first executive officers were also listed.

Lastly, the fifth article explained that the Young and True Friends would have full authority to acquire any kinds of property and effects as long as the value did not exceed $300,000.

According to a 1997 article in the Times Picayune, the Young and True Friends Benevolent Association once had up to 500 members and was one of the largest associations in New Orleans. By 1997, the society was down to 35 members whose membership dues were used to maintain their three burial plots in the Carrollton Cemetery.14

Another aspect related to benevolent groups are the parades, locally and fondly referred to as Second Lines. Parading in the streets of New Orleans dates back to the early history of the city and has become part of the culture as well as a tradition of benevolent associations and other types of clubs and organizations.15 Unfortunately, the Young and True Friends Benevolent Association stopped parading in 1994.16 However, their legacy lives on in a 1963 recording of a jazz funeral procession linked here: http://hnoc.minisisinc.com/thnoc/catalog/1/196971

The Young Men Olympian Junior Benevolent Association

Photo courtesy of Matthew Hinton via TheAdvocate.com

https://www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/news/article_d5f260c9-bb44-5404-ab8c-0fa4ee28dc7b.html

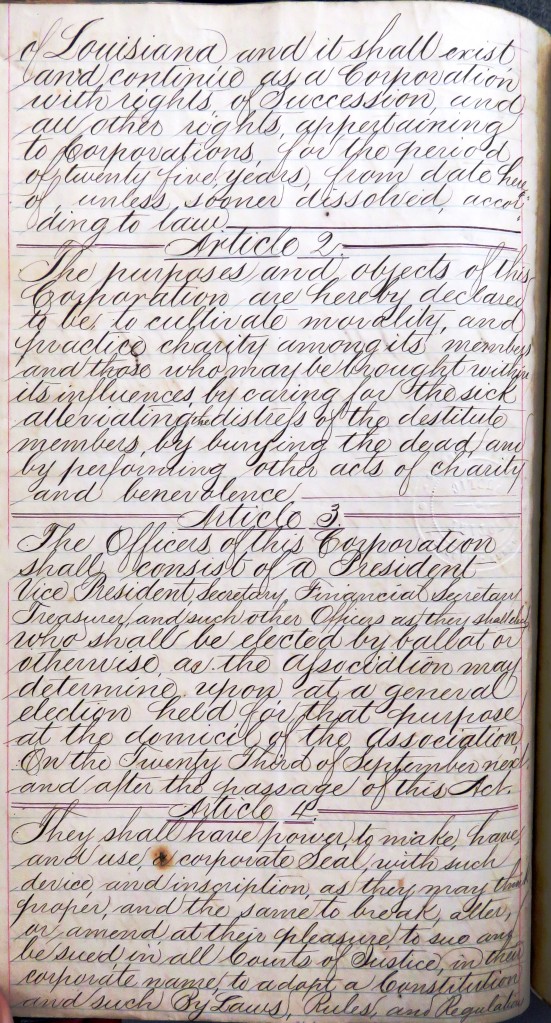

The Young Men Olympian Junior Benevolent Association prides itself on being one of the oldest still active benevolent societies and the last association still parading in New Orleans.17 As seen on the banner in the image above, the association formed on September 3, 1884. They officially chartered the association on August 25, 1885 in the act below.

The association appeared before notary, Henry J. Rhodes, to charter their organization with the name “Young Men’s Olympian Benevolent Association Juniors” of New Orleans.

Article One states that the association was to exist for a “period of twenty-five years, from date here of, unless sooner dissolved, according to the law.” However, during September 2021, the association will celebrate its 137th year anniversary.

The purpose of the society, as declared in Article Two, was “to cultivate morality and practice charity among its members and to those who may be brought within its influences, by caring for the sick, alleviating the distress of the destitute members, by burying the dead, and by performing other acts of charity and benevolence.”

The remainder of the charter explains that the association was granted the right to “break, alter, or amend at their pleasure, to sue and be sued… to take, receive, and hold all manner of lands, …to use, lease, employ, sell, or dispose of the same…” and all other rights and privileges that were conferred with the act of incorporation.

All members present signed the charter with the notary and witnesses. The reader may notice the notary’s final remark mentioning one member’s inability to sign his name and the omission of a word in the organization’s name. The note states, “At the time of signing the act, Edward Wilkins not being able to write his name, has placed his mark thereto in presence of the witnesses above named. ‘Men’s’ inserted in the title [of the charter] was approved before signing.”

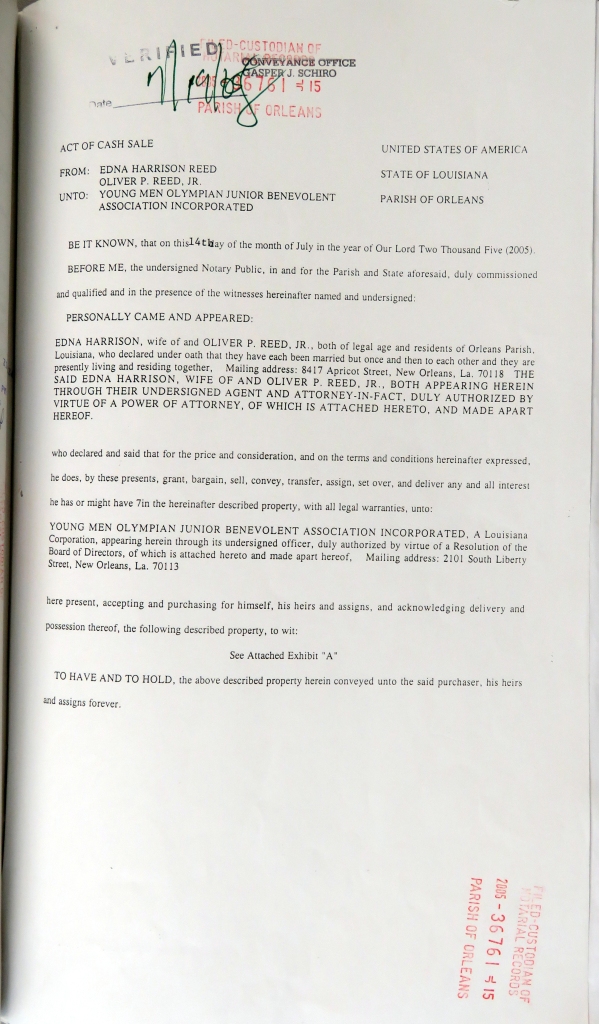

In addition to the charter, a more recent notarial act identifies where the Young Men Olympian Junior Benevolent Association acquired their current clubhouse.

Image via Google Maps, 2019.

In the act of sale below, the Young Men Olympian Junior Benevolent Association acquired property from Edna and Oliver Reed on July 14, 2005.

The legal description below states that the property is located in the Fourth District, “designated as lot 12, square 325, bounded by South Liberty Street, Josephine Street (side), LaSalle Street (side) (late Howard), and Jackson Avenue.” The municipal address is 2101-03 South Liberty Street in New Orleans.

Attached to the act of sale is an excerpt from the minutes of the association’s board of directors meeting. The minutes provide the names of the officers who had been authorized to “purchase, exchange, and/or sell real property…” In this case, the parties were Joseph Allen, Jr., the treasurer, and Norman Dixon, Jr., the president who is still presiding over the association to date.

As previously mentioned, it was common for benevolent societies to purchase tombs to bury their members. Young Men Olympian Junior was no exception. The association owns two tombs in Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. According to the records housed at the Division of Cemeteries, part of the City’s Department of Property Management, the tombs were purchased by the Young Men Olympian Junior Benevolent Association in 1893 and 1894, one of which was likely purchased from a previously dissolved benevolent association as evidenced by the dates in the picture below.

Photo courtesy of John McCusker via Nola.com

Vaults broken into, remains exposed at New Orleans’ historic Lafayette cemetery | News | nola.com

Interestingly, the Young Men Olympian Junior Benevolent Association held its first grand ball on January 8, 1900, for the benefit of their tomb fund. The flyer for the ball is pictured below.

https://exhibits.tulane.edu/exhibit/jazz-posters/soiree_dansante/

The ball was held at the corner of Perdido and Rampart Streets at what was then the Masonic and Odd Fellows Hall, belonging to two other fraternal benevolent associations. The flyer also states that music would be provided by “the Peoples Favorite Robichaux’s Imperial Orchestra,” which was led by John Robichaux (pictured below). Robichaux was known for his “classy” music and playing at “…society balls and fashionable restaurants and hotels.”18

https://www.nps.gov/people/john-robichaux.htm

Today, the Young Men Olympian Benevolent Association “…adheres most closely with its nineteenth century ancestors, offering burial in society-owned tombs, funerals with music, and medical and financial assistance.”19 The Norman Dixon, Sr. Annual Second Line Parade Fund was founded in 2003 by former president, Norman Dixon Sr. (the father of current president Norman Dixon Jr.). The fund “provides assistance to the Social Aid & Pleasure Club and Mardi Gras Indian communities with direct grants to cover the expenses associated with their public parading in New Orleans…[which] impacts over 3,000 Social Aid & Pleasure Club members in some 40 organizations…”20 In addition to their acts of benevolence, they still “second line” every September as part of the parade season that runs on Sundays from August to June to honor their history, heritage, and traditions.

Photo by Kim Welsh via Offbeat.com

https://www.offbeat.com/news/young-men-olympian-junior-benevolent-association-second-line-photo-slideshow/

Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs

Social aid and pleasure clubs evolved from benevolent associations, beginning in the early 1900s. The popularity of benevolent societies began to fade around the 1930s during the Great Depression when it became harder to pay membership dues and public assistance became more accessible.21 As a result, clubs began to focus on social activities and parading “…while providing some financial aid.”22 Organizations, many of whom readers can still recognize today, like Jugs and Zulu, began chartering as social aid and pleasure clubs at this time.

Prince of Wales Social Aid and Pleasure Club

Another such club whose original charter can be located in the Clerk’s Office is the Prince of Wales Social Aid and Pleasure Club.

The Prince of Wales Social Aid and Pleasure Club hails from the Irish Channel area of the city and was established by “dock and rail yard workers from the wharves and rail lines along Tchoupitoulas Street. There are two theories as to the origin of the club’s name. One suggests that the club members all drank J&B scotch, whose bottles pay tribute to the Prince of Wales. The other points to a visit to New Orleans by the Prince of Wales in the late 1920s, whose dress and sophisticated image inspired the club’s founders.”23

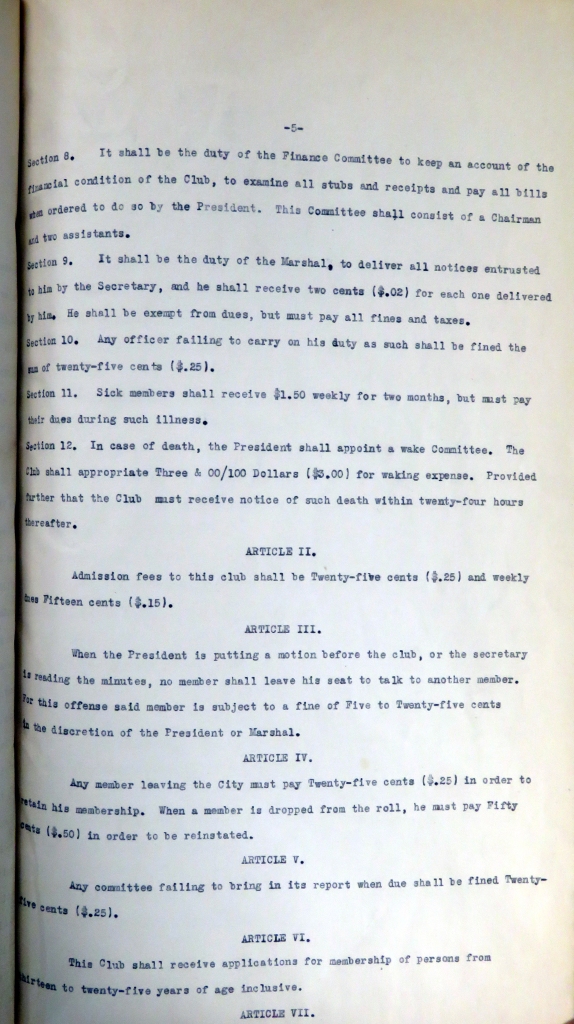

On May 1, 1929, the Prince of Wales Social Aid and Pleasure Club came before notary, Harry Mayo Jr., to charter their organization and record their by-laws.

In Article Three above, the purpose of the social club was to “…aid one another when in distress; to give entertainments and other functions for the amusement of its members, and perform all that a corporation of its kind is permitted to do by law.” The language and purpose of this social aid and pleasure club differs from the previous benevolent association examples with the emphasis on entertainment and social engagement instead of mutual aid and charity as its main focus.

The remainder of the act above follows the standard language and format of a charter. However, this is the first instance discussed here where by-laws have been included in the act as featured below.

The first several sections cover the financial matters, such as the handling of money and who was required to pay dues, taxes, and fines in the organization. The duties of the club’s officers and committee members are defined. Examples of duties include that the chaplain must open and close all meetings with a prayer, and the sick committee had to visit the sick twice a week and “make a report to the club.”

The remaining by-laws cover several topics such as how members are to conduct themselves (Article XV p. 6, XII, XIII), when the anniversary supper is held (Article XIII), and the oath the members are to take (Article XV p. 7).

The Prince of Wales Social Club is still active and typically parades in the month of October.

It’s obvious since the inception of the city that New Orleans has a deep love for a good party and social connections, which can be seen through the enduring history of parading, benevolent societies, and social aid and pleasure clubs. But beyond the pomp and circumstance, there is the emotional and spiritual connection to longstanding traditions and heritage that have been engrained into the heart and culture of New Orleans.

The Clerk’s Office has a rich amount of history pertaining to benevolent associations and social aid and pleasure clubs. If there are any particular interests that you would like to learn about, please contact the Clerk’s Office. We are happy to assist.

Sources:

1 NY Historical Society Museum and Library. “Women and the American Story Resource 10: Benevolent Societies.” NY Historical Society , 2017. https://www.nyhistory.org/sites/default/files/newfiles/cwh-curriculum/Module%202/Resources/Resource%2010%20Benevolent%20Societies.pdf

2 Jacobs, Claude F. “Benevolent Societies of New Orleans Blacks during the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, vol. 29, no. 1, 1988, pp. 22. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4232632.

5 https://www.greenwoodnola.com/

6 Seiferth, Eric. “Pleasure, Principled.” The Historic New Orleans Collection Quarterly, vol. XXXVIII, no. 1/2, Winter/Spring 2021. pp. 3

7 “Benevolent Associations .” Encyclopedia of the New American Nation. Encyclopedia.com. 16 Jun. 2021 <https://www.encyclopedia.com>.

8 NY Historical Society Museum and Library. “Women and the American Story Resource 10: Benevolent Societies.” NY Historical Society, 2017. https://www.nyhistory.org/sites/default/files/newfiles/cwh-curriculum/Module%202/Resources/Resource%2010%20Benevolent%20Societies.pdf

9 Dedek, Peter B. The Cemeteries of New Orleans: a Cultural History. Louisiana State University Press, 2017. pp. 90

10 Seiferth, Eric. “Pleasure, Principled.” The Historic New Orleans Collection Quarterly, vol. XXXVIII, no. 1/2, Winter/Spring 2021. pp. 3-4

11 Dedek, Peter B. The Cemeteries of New Orleans: a Cultural History. Louisiana State University Press, 2017. pp. 89

12 Dedek, Peter B. The Cemeteries of New Orleans: a Cultural History. Louisiana State University Press, 2017. pp. 89

13 Seiferth, Eric. “Pleasure, Principled.” The Historic New Orleans Collection Quarterly, vol. XXXVIII, no. 1/2, Winter/Spring 2021. pp. 3

14 “A Caring Tradition at Twilight.” Times-Picayune, 24 Aug. 1997, p. 20. NewsBank: America’s News – Historical and Current, infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1223BCE5B718A166%40EANX-NB-16EF5EA770C296C6%402450685-16EED8D80FC22DD3%4019.

15 Seiferth, Eric. “Pleasure, Principled.” The Historic New Orleans Collection Quarterly, vol. XXXVIII, no. 1/2, Winter/Spring 2021. pp. 3

16 “A Caring Tradition at Twilight.” Times-Picayune, 24 Aug. 1997, p. 20. NewsBank: America’s News – Historical and Current, infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A1223BCE5B718A166%40EANX-NB-16EF5EA770C296C6%402450685-16EED8D80FC22DD3%4019.

18 Davis, Ronald L. “Early Jazz: Another Look.” Southwest Review, vol. 58, no. 1, 1973, pp. 1–13. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43468459. Accessed 24 June 2021.

19 Sundays in the Streets – Southern Cultures

21 Seiferth, Eric. “Pleasure, Principled.” The Historic New Orleans Collection Quarterly, vol. XXXVIII, no. 1/2, Winter/Spring 2021. pp. 4

22 Jacobs, Claude F. “Benevolent Societies of New Orleans Blacks during the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, vol. 29, no. 1, 1988, pp. 22. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4232632.

23 https://mattsakakeeny.com/roll-with-it/funerals-and-parades/prince-of-wales/

Great article. Whew, that took a lot of hours of research.

LikeLike

AWESOME RESEARCH, THANKS…as a club member and current Business Manager of POW..Great Job. Thanks Stan Taylor

LikeLike